Rare Earth Race

In the AI race, it is all about the power of processors (TPUs or GPUs) and chips. But what all of those are driven by is rare earths, which have entered the race as well.

US companies are snapping up critical rare earths, especially those for defense, outbidding European firms to secure supplies and funnel them into components to limit scrutiny from China, which may retaliate with export license restrictions.

Still, the exact impact on the US’s rare earth stockpile is unknown currently. The Pentagon and private companies like MP Materials, Lynas, and ReElement Technologies are supplying hundreds to thousands of tonnes of rare earth oxides annually, with defense needs requiring ~400 tonnes of dysprosium per year.

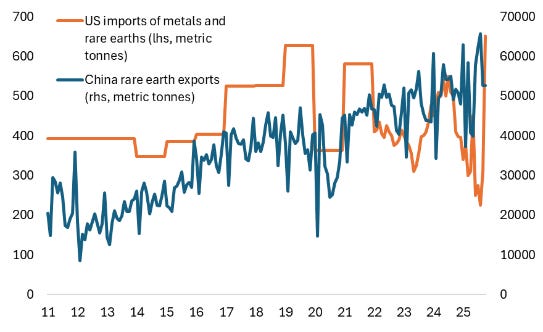

China controls ~90% of global rare-earth processing capacity, leaving the U.S. dependent on imports. Year to date, China exported 38,563.6 metric tonnes of rare earths in the first seven months of 2025 — a 13% increase compared to the same period in 2024.

Germany was the largest buyer of Chinese rare earths, but the US ranks second with imports surging in October 2025 to a nine‑month high (656 tonnes of magnets, +56% month‑over‑month). Global demand for rare earths is rising, potentially creating shortages as countries scramble to secure stockpiles.

Figure 1: Rare earth exports and imports (metric tonnes)

Source: Commerce Department

According to the Pentagon and the GAO, the U.S. defense sector is most at risk of a rare earths shortage between now and 2027, when procurement bans on Chinese supply take effect, but domestic production is still ramping up. If Pentagon‑backed projects slip past 2028, the U.S. could face severe bottlenecks in fighter jet, missile, and submarine production.

In July, the Pentagon launched a new strategic initiative to secure rare earths for defense, setting a minimum annual target of ~400 tonnes of dysprosium.

According to the GAO, the Department of Defense has limited influence over the rare earths market, even though defense-specific rare earths account for less than 0.1 percent of global demand. Nonetheless, the urgency at the Pentagon to act has risen significantly since the summer, when China suspended export licenses.

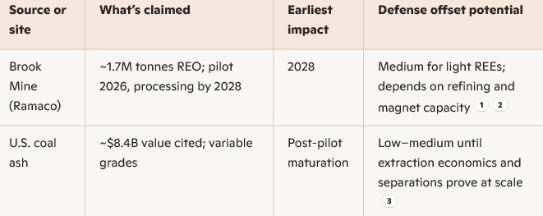

Figure 2: Rare earths used in defense

Source: GAO

An investment of $2.8 billion between 2025-2028, consisting of $400 million equity stake in MP Materials and $1.4 billion partnership with Vulcan Elements. The Pentagon and MP Materials also announced a rare earths refinery in Saudi Arabia with state-owned Ma’aden, also split: Pentagon + MP (49%), Ma’aden (51%).

Still, there is pressure to meet the minimum target, which would not reduce reliance on China. By 2026, Vulcan Elements must prove commercial viability, and by 2028, MP’s magnet facility is expected to be online, before China can reimpose export restrictions.

While there is some relief on the cyclical horizon, the newest rare earth pockets in the U.S. were discovered in Alaska and Wyoming, with additional potential resources identified in coal ash deposits across several states.

Mining company Graphite One announced in November 2025 that its Graphite Creek deposit contains significant rare earth elements (REEs) alongside graphite.

Elements identified include neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, terbium, and samarium — all critical for permanent magnets used in wind turbines, EVs, radar, and precision-guided munitions. This dual deposit (graphite + REEs) is considered a Defense Production Act Title III material site, underscoring its national security importance.

In July 2025, the U.S. Energy Department confirmed massive, rare-earth oxide deposits at the Brook Mine. This is the first significant U.S. rare earth discovery in over 70 years, with estimates valuing the deposit at up to $37 billion.

Research from the University of Texas (2024–2025) found that coal ash from power plants may contain up to $97 billion in extractable rare earths. States with large coal ash reserves (e.g., West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Texas) could become secondary sources of REEs.

Still, these pockets may not have sufficient rare earths needed for defense. Instead, they are mostly “flakes” that would not meet the minimum floor of 400 metric tonnes. The Minebrook deposit is estimated at up to 1.7 million tonnes of rare earth oxides, with the developer targeting pilot operations in 2026 and complete refining/processing around 2028.

Refining and separation capacity in the U.S. and allied countries remains limited. Without non-Chinese refining for light and heavy REEs, oxide tonnage cannot be converted into the defense-grade products required for jets, missiles, and submarines. Dysprosium and terbium (for high-temperature, high-coercivity magnets in F-35s and other defense weapons) will remain the acute bottlenecks.

Table 1: Minebrook and ashes

Source: Ramaco Resources

OpenAI, Anthropic, Amazon, and Google do not mine rare earths, but their AI models and cloud platforms cannot operate without them.

Rare earths are embedded in GPUs, servers, cooling systems, and consumer devices that enable AI. As these firms expand their AI infrastructure, their reliance on rare-earth supply chains—dominated by China—becomes a strategic vulnerability.

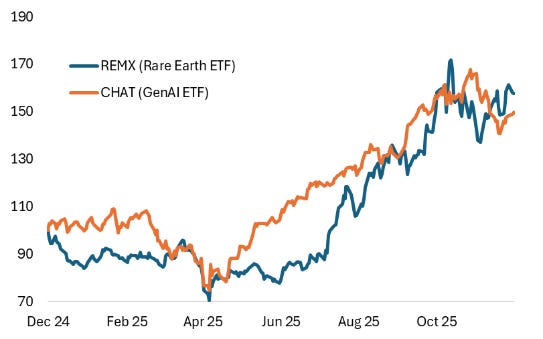

The rare earth race is squarely on (!)—the rare earth ETF and GenAI ETF are entangled in a race to finish, even though GenAI cannot exist without rare earth inputs.

Figure 3: REMX vs. CHAT

Source: VanEck, Roundhill

Excellent breakdown of how rare eath supply chains are becoming a critical defense vulnerability. The timing bottleneck you mentoin is particularly striking, with domestic production needing to scale by 2028 but China potentially reimposing restrictions before then. The coal ash option is interesting becuase it turns an environmental liability into a strategic asset, though the extraction economics arent fully proven yet at the volumes defense needs.